Science, You’re Super: Bees!

By Aryn Henning Nichols • Photo by Evan Sowder

Originally published in the Summer 2015 Inspire(d)

There’s always been a buzz around bees.

Okay…it’s a bad pun. But, really, bees are pretty darn amazing. They fly their slightly cantankerous (especially for the bumble bees) bodies around, pollinating flowers and crops across the world – in the U.S., alone, their work is worth an estimated $10 billion. (3)

Some even say bees are responsible for one out of every three bites of food we eat. Most crops grown for their fruits (like squash, cucumber, tomato, eggplant), nuts, seeds, fiber (such as cotton), and hay (alfalfa grown to feed livestock), require pollination by insects. Pollination is “the transfer of pollen from the male parts of a flower to the female parts of a flower of the same species, which results in fertilization of plant ovaries and the production of seeds.” According to Michigan State University’s entomology department, the main insect pollinators, by far, are bees. There are hundreds of species of bees that contribute to the pollination of crops. (5)

So where do these little super heroes come from and how do they know how to do their jobs?

Scientists believe that both bees and flowering plants evolved around 100 million years ago during the Cretaceous period. Before this, many plants released seeds and pollen using cones (think pine trees, but both big and small cones). The wind brought the pollen and cones together, thus fertilizing them. But some plants began to reproduce using flowers, and they needed the help of insects and other animals to achieve pollination. (2)

Around the same time, bees were evolving from their wasp-like ancestors. Prehistoric wasps were carnivores that lay their eggs in the bodies of their prey. After flower reproduction happened, bees became herbivores, eating pollen and nectar from the plants and pollinating flowers as they went. (2)

To further enhance pollination, a bee’s body is covered in fuzzy hair that collects pollen, and its legs are built for specific pollen-collecting tasks. The body has three sections – the head, the thorax and the abdomen – much like other insects. The abdomen houses the stinger, and the crop, or honey stomach, where the bees store nectar. A bee has five eyes – three simple eyes, “orocelli”, and two compound eyes made of lots of small, repeating eye parts called “ommatidia” that specialize in seeing patterns. This allows bees to detect polarized light – a super-power humans do not possess! (2)

Bees can be solitary – living mainly alone – or social – living in colonies. Less than 15 percent of bees are social, even though many people are most familiar with social bees since they produce things like honey and beeswax, and will pollinate in large groups in orchards and gardens. (2)

Two of the most advanced social bees are honeybees and bumblebees. Each colony has a single queen, many workers, and – at certain stages in the colony cycle – drones. A commercial – human provided – honeybee hive can contain up to 40,000 bees at their annual spring peak (but it’s usually fewer). (1)

Although honeybees and bumblebees are both social, their societies are quite different. Honeybee colonies are perennial – a nest will last generations. Bumblebees, on the other hand, have annual nests. (2) But no matter how they live, most bees have a similar approach to mating. In nearly every species, a male bee’s only job is to mate with a female. After the female mates, she either retreats to a shelter for the winter or returns to her nest to lay eggs. A female solitary bee lays only a few eggs in her lifetime, but a queen honeybee lays thousands! (2)

Honey, let’s Dance

Bees have an acute sense of smell, and can recognize symmetry and patterns, such as colors or shapes. This helps bees find and recognize flowers and food. Honeybees communicate food’s location with a special bee language: dancing.

When a scout finds food, she uses two known tools to remember its location. 1. A solar compass that helps her calculate where things are in relation to the sun. The bee’s ability to see polarized light (remember the ommatidia eyes) tells her where the sun is even if it’s a cloudy day. 2. An internal clock that tells her how far she has flown.

When the scout returns to the hive, she distributes nectar samples, then performs a dance on the hive “dance floor.”

If the food is nearby, the scout does a “round dance,” making loops in alternating directions.

When the food is far away, she does a “waggle dance”. She runs in a straight line while waggling her abdomen, then returns to the starting point by running in a curve to the left or right of the line. The straight line indicates the direction of the food in relation to the sun. (3)

Then, the sisters head out to forage. They make up to a dozen trips back and forth between the hive and the food; each bee can carry half her weight in pollen or nectar!

Inside the hive, the worker bees transform the nectar into honey. Nectar is 70 percent water compared to honey’s 20 percent. Bees evaporate the extra water by regurgitating the nectar over and over, and also fan their wings over the honeycomb.

While doing all this foraging for nectar and pollen, bees inadvertently pollinate nearly 100 crops. All told, insect pollinators contribute to one-third of the world’s diet. (3) (Super heroes!)

Bees themselves gather enough honey to survive winter. During winter, bees leave their hives only to go to the bathroom. Inside, they take care of the queen and heat the hive by vibrating their wing muscles, similar to humans’ shivering. To control the temperature in the summer they circulate air with their wings and sprinkle the honeycomb with water. (3)

The length of a female honeybee’s life is usually only a few weeks. A queen, though, can live three to five years!

There has been a major decline in commercial honeybee numbers over the past 50 years – and even more so since 2007 – called Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). The cause hasn’t been pinpointed yet, but researchers say reasons could include parasites and bacteria, environmental stress, like a lack of pollen, and, very likely, pesticide usage.

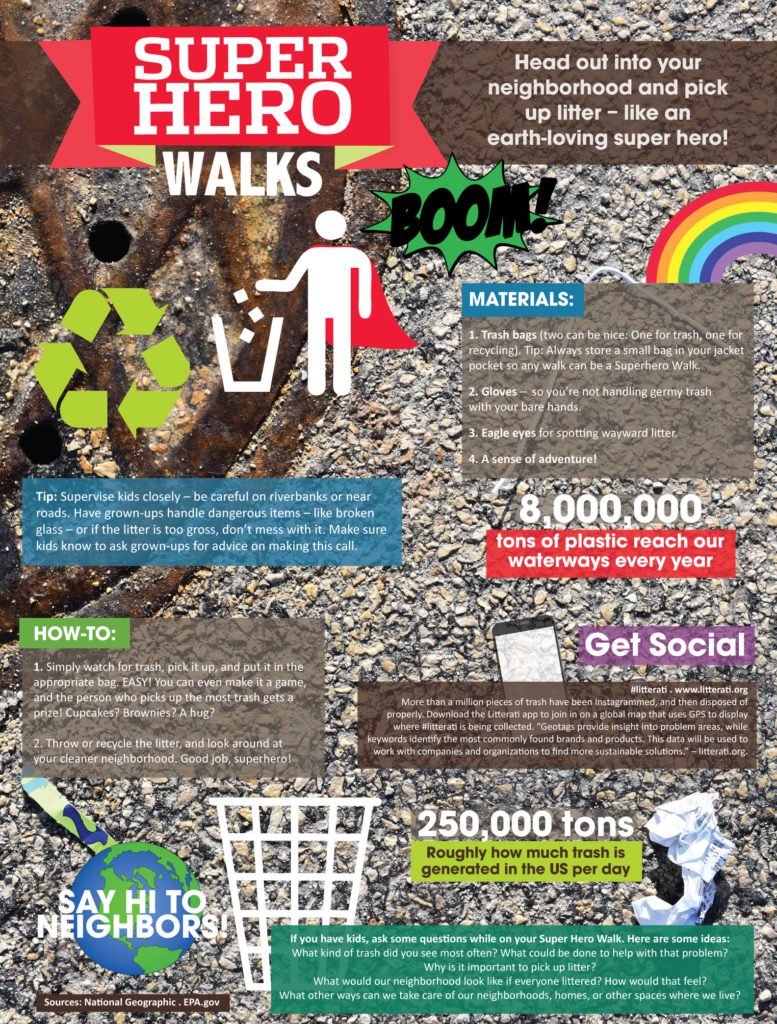

What can we do to help? Here are three easy ideas:

- Plant a Pollinator Garden. See online guide for plantings. (www.pollinator.org/guides.htm)

- Reduce your use of pesticides, especially when flowers are in bloom and bees are out foraging

- Buy local to help support local beekeepers (4)

—————————

Aryn Henning Nichols was amazed by bees as she researched this story – dancing? Polarized light? Awesome. Let’s work to save the bees! Plant some butterfly weed (and other pollinator garden plants) today!

Extra bee facts:

- The average American consumes a little over one pound of honey a year.

- In the course of her lifetime, a worker bee will produce 1/12th of a teaspoon of honey.

- To make one pound of honey, workers in a hive fly 55,000 miles and tap two million flowers.

- In a single collecting trip, a worker will visit between 50 and 100 flowers.

- A productive hive can make and store up to two pounds of honey a day. Thirty-five pounds of honey provides enough energy for a small colony to survive the winter. (3)

Sources:

1. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bee

2. animals.howstuffworks.com/insects/bee.htm

3. www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/bees/

4. www.cnn.com/2015/03/04/living/iyw-5-ways-to-help-bees/

5. nativeplants.msu.edu/about/pollination