One ‘Tuft’ bird

The largest of five owl species that breed in the Driftless Area, Great Horned Owls are also the most common. Found from Alaska to Argentina, they are habitat generalists, equally at home in oak woodlands, suburban yards or urban parks. Their pronounced “ear tufts” – modified head feathers – create the bird’s iconic silhouette.

Courtship begins in early autumn. The characteristic, stuttering “hoo-hoo-hoo” that gave rise to the moniker “hoot owl” can be heard in September. By October, the duet of paired owls resonates through leafless woodlands as the birds proclaim fidelity and publicly announce their intention to raise a family.

Nest site selection begins even as daylength diminishes. Not one to waste energy with winter nest construction – wise owl? – the female Great Horned Owl typically appropriates old stick nests from Red-tailed Hawks or crows. Large tree cavities or the ragged tops of broken tree trunks can also provide suitable digs.

By the end of January, contrary to every lick of common sense, the female carefully deposits as many as four eggs in the nest. Over the next four weeks, she will tend her eggs while the male brings her food. It’s not uncommon to see a snow-covered female hunkered and incubating during raging blizzards, signature ear tufts twisting in the wind. As the landscape remains draped in white, little owlets hatch naked, blind, and hungry. Overnight, mom transforms from a doting parent to a voracious hunter, partnering with her mate to feed their brood of squawking owlets.

Great Horned Owls are among the most efficient predators on earth. They prowl the darkness aided by keen eyesight and extraordinary hearing. Serrated combs of small feathers on the leading edge of their wings enable silent flight, facilitating their ability to ambush unsuspecting prey.

Equal opportunity carnivores, hoot owls eat just about anything they can catch. Rats, mice, rabbits, and squirrels are dietary staples. On occasion, frogs, snakes, and birds land on the menu. For reasons not fully understood, Great Horned Owls have a predilection for skunks. Perhaps an owl’s poor sense of smell protects it from the olfactory vicissitudes of Pepé Le Pew and his ilk.

After 40 days of constant care, young owls leave the nest. They’ll spend the summer shadowing mom and dad, learning how and where to hunt. By fall, they drift away from parents and siblings. Another year will pass before they’re ready to seek a mate and begin the cycle anew.

The secretive, nocturnal lives of these feathered phantoms add an element of mystique to our woodlands. But their importance transcends folklore. Predators are essential for functional ecosystems. By keeping populations of rodents and other small mammals in check, Great-horned Owls contribute to the health of our natural communities. Next time you retire for the evening, turn off the lights, crack a window, and listen for the Great-horned Owl. It will be a hoot!

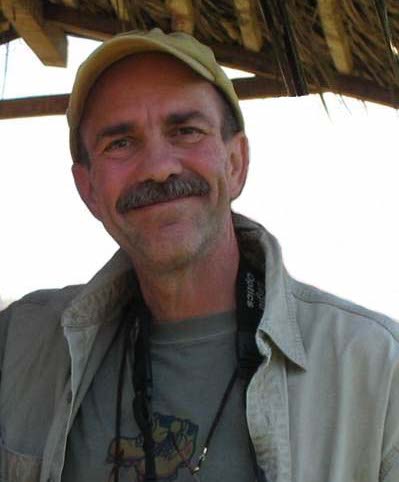

Craig Thompson

Craig Thompson is a professional biologist with a penchant for birds dating back to a time when gas was $0.86 cents a gallon. He hopes never to see skunk on his menu.

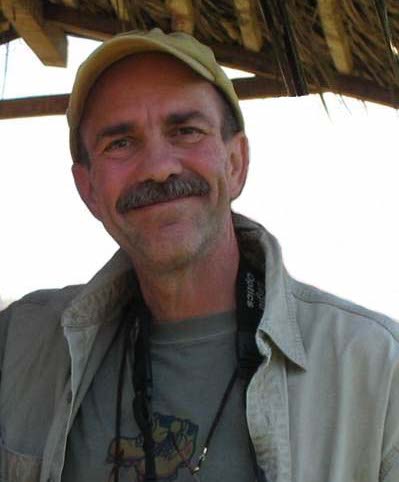

Mary Thompson

Mary Thompson has degrees in Fine Arts and Education. She has delighted in the creative arts since her first box of crayons. She believes winter is the season for hoots and boots.